If you struggle to take your dog out in public, on a walk, for a car ride, or even enjoy a quiet day at home because your dog is constantly barking at other dogs or people, you aren’t alone.

Reactive behavior —typically barking, growling, or lunging at other dogs, people, or other stimuli — can be frustrating, scary, and disruptive, but it’s also common and normal. No matter the size, breed, or age of your dog, understanding why your dog presents reactive behavior is the first step to changing that behavior.

Reactivity is a symptom

Your dog’s behavior always has a purpose. When a dog displays reactive behavior, it isn’t because they’re “bad” or trying to give you a hard time. Rather, they are experiencing a big emotion, like fear, frustration, or pain, and reactivity is the only tool that they have to communicate those feelings with you and others around them.

Fear

A dog who is scared, nervous, or uncertain is likely to display reactivity when they’re on leash or otherwise restrained, because the option to move away from whatever is making them uncomfortable has been removed. This is extremely common in dogs who are under-socialized, have had a scary experience in the past (e.g. another dog bit them, a stranger put them in an uncomfortable position), or who have generalized anxiety.

Frustration

Reactivity based in frustration is common in dogs who do enjoy the company of other dogs or people in some situations, but do not have the tools to properly greet others or to exist in the same space as others without greeting. Your dog may display reactivity on leash or behind a barrier, such as a fence, that prevents them from access to others. This is especially common in dogs who attend day care, dog parks, or other spaces in which they have unrestricted access to others.

Pain

Pain and physical discomfort may be the most overlooked cause of reactivity, because pain often goes unrecognized in dogs until it has escalated. Dogs with chronic pain (e.g. joint pain, improperly healed injuries), acute pain, illness, or allergies may display reactive behavior with both known and unknown people and dogs. You may feel like your dog has had a sudden change in behavior or is displaying reactivity in situations that they previously enjoyed.

Reactivity works

From your dog’s perspective, reactive behavior is effective. Because they are fearful, frustrated, painful, or otherwise uncomfortable, your dog uses reactivity to demand space from those around them. In most cases, barking, growling, or lunging at another dog or person does result in that dog or person going away, reinforcing the idea that displaying this behavior is the best way to create space. If that reactive behavior doesn’t work, and the other dog or person approaches, it typically proves to your dog that the other dog or person is in fact scary or harmful, often resulting in an escalation of behavior in the future. Because this behavior is self-reinforcing, it’s extremely important that we are addressing the root cause of the behavior for effective and long-term behavior change.

Safe and effective treatment for reactivity

Reactive behavior may be normal, but that doesn’t mean that you or your dog have to live with it. Changing your dog’s behavior won’t happen overnight, but you can start taking steps today to provide much-needed relief for both of you.

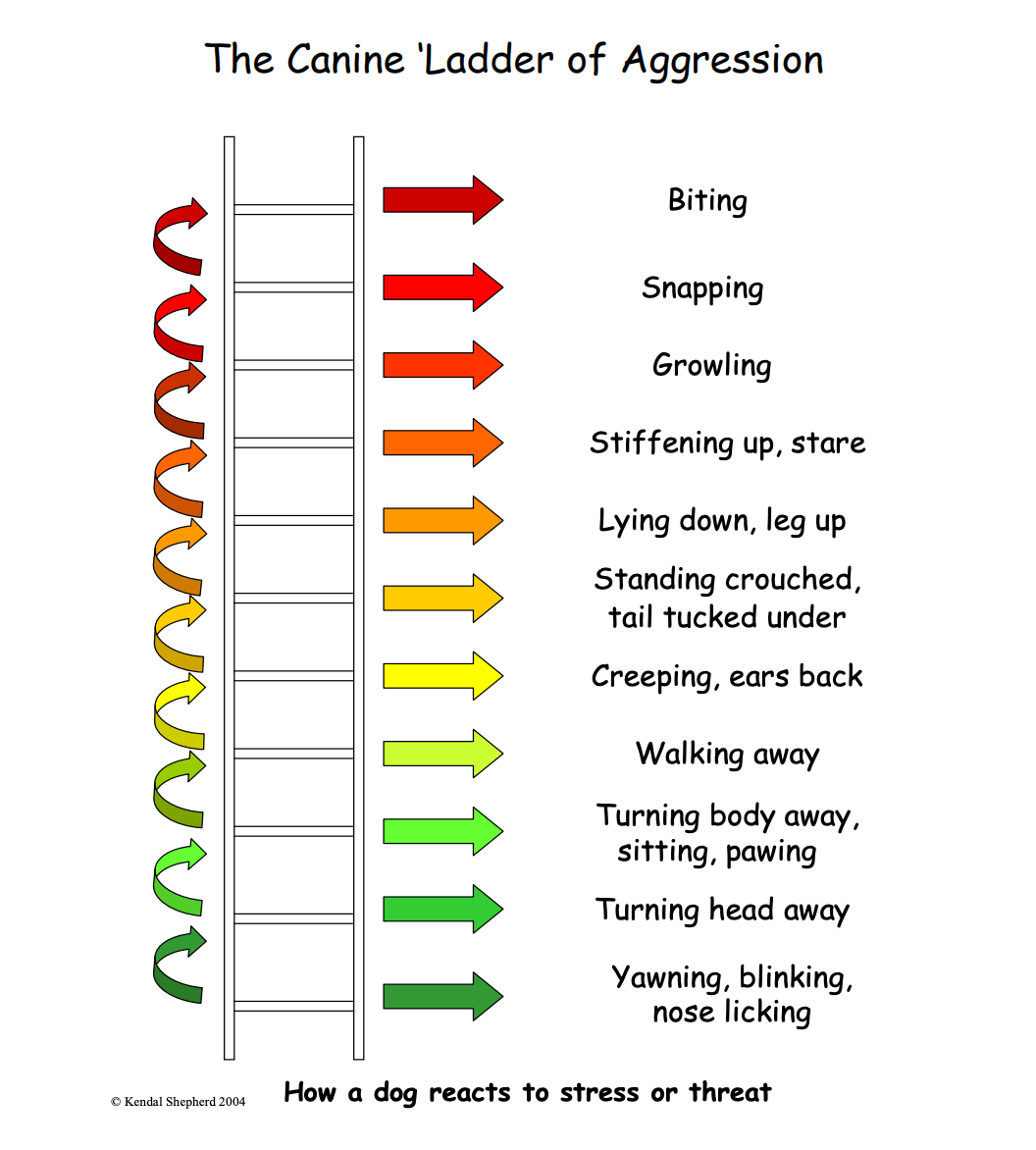

Dog body language & the ladder of aggression

Dogs primarily communicate through their body language, and learning to understand and respect what they are saying can help you prevent reactive behavior before it starts.

While every dog is an individual and will display signs of stress and discomfort in different ways, the ladder of aggression (below) is a great resource for understanding subtle communication. The more that you pick up on these early behaviors and help your dog navigate the situation, the more that they will display those behaviors before resorting to reactivity — and the more that your dog will trust that you have their back.

Take the time to observe your dog’s behavior when something that they would typically react to is at a distance. Do they start licking their lips, tuck their ears back, avoid eye contact, or turn their body away? What happens when you encourage them to move in the other direction? Knowing which behaviors your individual dog is most likely to display will help their behavior feel more predictable and preventable.

Medical intervention

If your dog is regularly displaying reactive behavior — or seems to have suddenly started to display reactive behavior — a trip to the vet is a must. Even seemingly minor medical issues can be a catalyst for reactivity, and addressing those issues with your vet as early as possible is vital to effectively changing your dog’s behavior.

Just like people, dogs can also suffer from anxiety, depression, and other mental health struggles. Your vet can help you identify if this is a potential factor for your dog, and, if so, may recommend lifestyle changes or trying a behavioral medication. These medications can be either situational (given prior to stressful events, like going to the vet) or used daily. Behavioral medicine is a specialized practice, so your usual vet may refer you to a veterinary behaviorist — just like your GP or family doctor may refer you to a psychologist, who has the tools and knowledge to better support you. Not every dog who displays reactive behavior needs behavioral medication, but it can be an incredible tool that elevates a dog’s ability to respond to training.

Punishment will eventually result in an escalation in behavior

Do not confuse reactive behavior with disobedience or “being bad.” Because reactive behavior is a symptom of underlying discomfort, simply using punishment or “correction” to stop the behavior will almost certainly backfire. These practices may seem to work in the moment — your dog may stop barking or growling when uncomfortable — but without treating those underlying causes, what you’re actually doing is creating a dog who will bite “without warning” to create distance from whatever or whoever is making them uncomfortable.

Use of shock collars (even on the beep or vibrate setting), choke collars, prong collars, leash corrections, yelling, hitting, isolation, and any other punishment is antiquated and unproductive. Your dog needs your support, not punishment.

Getting started with training

Effectively modifying your dogs behavior relies on changing their Conditioned Emotional Response. A dog who is displaying reactive behavior has a negative association with whatever is making them uncomfortable; we want to change that response to one of neutrality.

Think of Pavlov’s Dogs. The sound of a bell predicted the delivery of food; soon, the sound of a bell resulted in salivation, even without food immediately present, because the dogs learned to associate the bell with food. With a reactive dog, we want whatever is currently making them uncomfortable to predict good things — distance, a yummy snack, a toy that they love. This is referred to as Classical Conditioning.

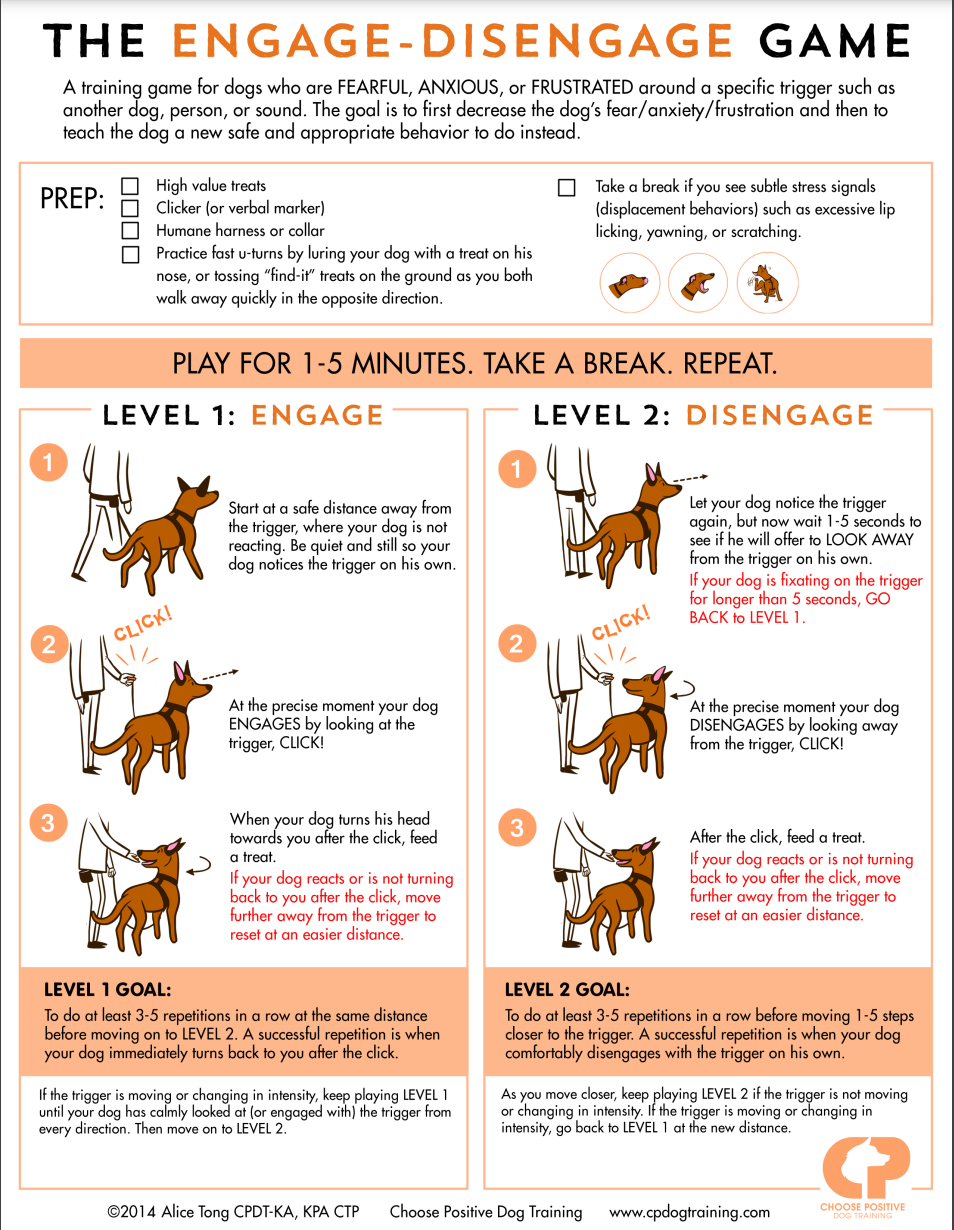

Once your dog begins to anticipate something good, you’ll begin to introduce Operant Conditioning, which helps them understand that their own behavior when faced with something that makes them uncomfortable will lead to those good things. The engage/disengage game (below) is popular place to start.

While this graphic recommends the use of a clicker, you can substitute a verbal marker, such as the word, “yes!” Introduce your marker in a quiet place in which your dog is calm and comfortable. Click or say, “yes!” and give your dog a treat when they look at you. Repeat this a few times, then ask your dog for a behavior that they already know, such as “sit.” When they perform the behavior, click or say, “yes!” and deliver the treat. Practice this a few times over the course of several days. Most dogs will quickly understand that the marker predicts reinforcement.

Food is typically an easy and effective choice for reinforcement, but it isn’t the only option. Other reinforcers may include play, praise, distance, sniffing, or access to other resources. What works best will depend on your individual dog and the behavior that you want to achieve.

Introducing management

‘Management’ refers to the things that you do to change your dog’s environment to prevent situations in which they will display reactivity. This may include only going for walks in quiet places free of other dogs or people, using window film to prevent your dog from seeing people walking by the house, playing white noise to dampen outdoor noise, replacing some physical activity with mental enrichment, and any other number of modifications.

Management is always best when paired with training, but many dogs will display a significant change in behavior with consistent management. Reducing the frequency in which your dog displays reactive behavior will help reduce their overall stress level, which makes training much more effective.

Becoming your dog’s #1 advocate

Above all else, you dog needs to know that they can trust you. They need to know that you are truly listening when they communicate their discomfort, and that you will help them navigate uncomfortable situations.

Sometimes, being your dog’s advocate can make you feel uncomfortable. It may require you to firmly say no when someone asks to pet your dog, to seek out a second opinion from a vet or behaviorist if you feel that your concerns have not been taken seriously, or to make modifications to your own daily routine. It may require you to recognize that activities that you wanted to do with your dog, such as taking your dog to the bar or attending dog-friendly events, isn’t a good fit for your dog. You may need to practice how you’ll handle certain situations before they come up, such as instructing friends on how to interact with your dog. In time, though, it will become more comfortable, and the effects are well worth it.

Finding professional help

Dog training is an unregulated industry, which means that anyone can market themself as a dog trainer, regardless of their experience and education. Unfortunately, this is all too common, and putting your trust into the wrong person can be detrimental to both you and your dog.

Keep an eye out for these red flags; if you notice them in your trainer, it’s time to find help elsewhere:

- Your trainer relies on punishment and/or aversive tools, including, but not limited to, shock collars (even on the beep or vibrate setting), choke collars, prong collars, leash corrections, yelling, hitting, alpha rolling, and isolation

- Your trainer subscribes to ‘Dominance Theory,’ the long-debunked belief that dogs are pack animals with specific ranks and who need an “alpha”

- Your trainer wants to replicate situations in which your dog displays reactive behaviors to “see the behavior for themself.” A qualified trainer will want to prevent the behavior as much as possible and can give you accurate and effective advice based on the behavior that you’ve witnessed

- Your trainer guarantees that you’ll see progress within a specific timeframe. All dogs are individuals, and your training journey should be based on what’s best for you and your dog, not an arbitrary deadline

- Your trainer pushes you to send your dog to a board and train program or otherwise allow them to handle your dog without you present

- Your trainer is not flexible, talks down to you, or does not adequately support you. An experienced and qualified trainer will be able to adjust training exercises, assign management recommendations, and provide explanations that best fit your and your dog’s needs

If you aren’t sure where to find a qualified trainer, the CCPDT and IAABC databases are a great place to start. If you do not have a qualified trainer near you, or if cost is prohibitive, video call consultations can be an excellent resource for reactivity.

If you feel that your dog may benefit from intervention through behavioral medicine, you can find a Board Certified Veterinary Behaviorist through the ACVB. Because this is a specialized practice, it can be quite cost prohibitive, and waitlists may be long, however, part of a BCVB’s mission is to consult with general practice veterinarians in their state. Your vet can start the process by reaching out to them directly. You may also consider switching to a general practice vet who is has Fear Free certification, as they are typically more equipped to work with dogs who need behavioral support.

Remember that certification does not guarantee that a professional is the right fit for you and your dog. It’s okay to get a second opinion (or a third, or a fourth) if you don’t feel that you are getting the support that you and your dog need.

Progress is not linear

Like all things in life, you and your dog will have ups and downs in your journey with reactivity. Some days, you’ll feel like your dog’s behavior has done a 180; other days, you’ll feel like you are back to square one. This is normal, and it does not mean that you have done anything wrong.

Consider keeping a written log to look back on when you’re feeling down. It can be hard to see your progress from day-to-day; seeing how your dog’s behavior has changed over weeks and months can be extremely motivating.

Remember, too, that you are not alone. You likely already know at least one person who is struggling with their dog’s reactivity, and there are plenty of others out there who have experiences that mirror yours.

Learning how to better understand your dog will undoubtedly have a positive influence on all aspects of your life together. Change doesn’t happen overnight, and there will be tough days, but, in the end, the journey is worth it.